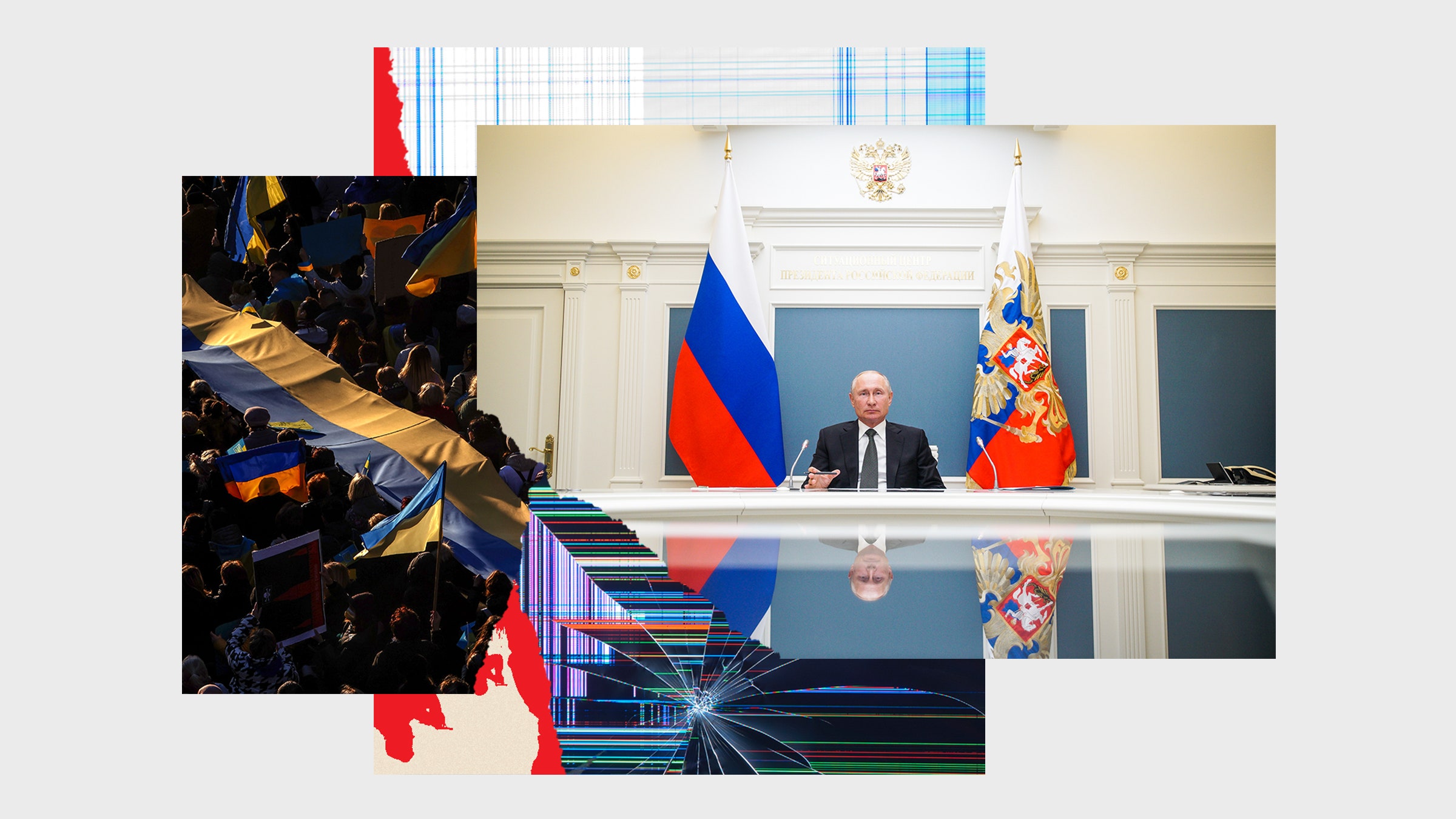

For decades now, Vladimir Putin has slowly, carefully, and stealthily curated online and offline networks of influence. These efforts have borne lucrative fruit, helping Russia become far more influential than a country so corrupt and institutionally fragile had any right to be. The Kremlin and its proxies had economic holdings across Europe and Africa that would shame some of the smaller 18th-century empires. It had a vast network of useful idiots that it helped get elected and could count on for support, and it controlled much of the day-to-day narrative in multiple countries through online disinformation. And many people had no idea.

While a few big events like the US’s 2016 election and the UK’s Brexit helped bring this meddling to light, many remained unaware or unwilling to accept that Putin’s disinformation machine was influencing them on a wide range of issues. Small groups of determined activists tried to convince the world that the Kremlin had infiltrated and manipulated the economies, politics, and psychology of much of the globe; these warnings were mostly met with silence or even ridicule.

Russia’s network of influence was as complex as it was sprawling. The Kremlin has spent millions in terms of dollars and hours in Europe alone, nurturing and fostering the populist right (Italy, Hungary, Slovenia), the far right (Austria, France, Slovakia), and even the far left (Cyprus, Greece, Germany). For years, elected politicians in these and other countries have been standing up for Russia’s interests and defending Russia’s transgressions, often peddling Putin’s narratives in the process. Meanwhile, on televisions, computers, and mobile screens across the globe, Kremlin-run media such as RT, Sputnik and a host of aligned blogs and “news” websites helped spread an alternative view of the real world. Though often marginal in terms of reach in and of themselves (with some notable exceptions, such as Sputnik Mundo), they performed a key role in spreading disinformation to audiences in and outside of Russia.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...