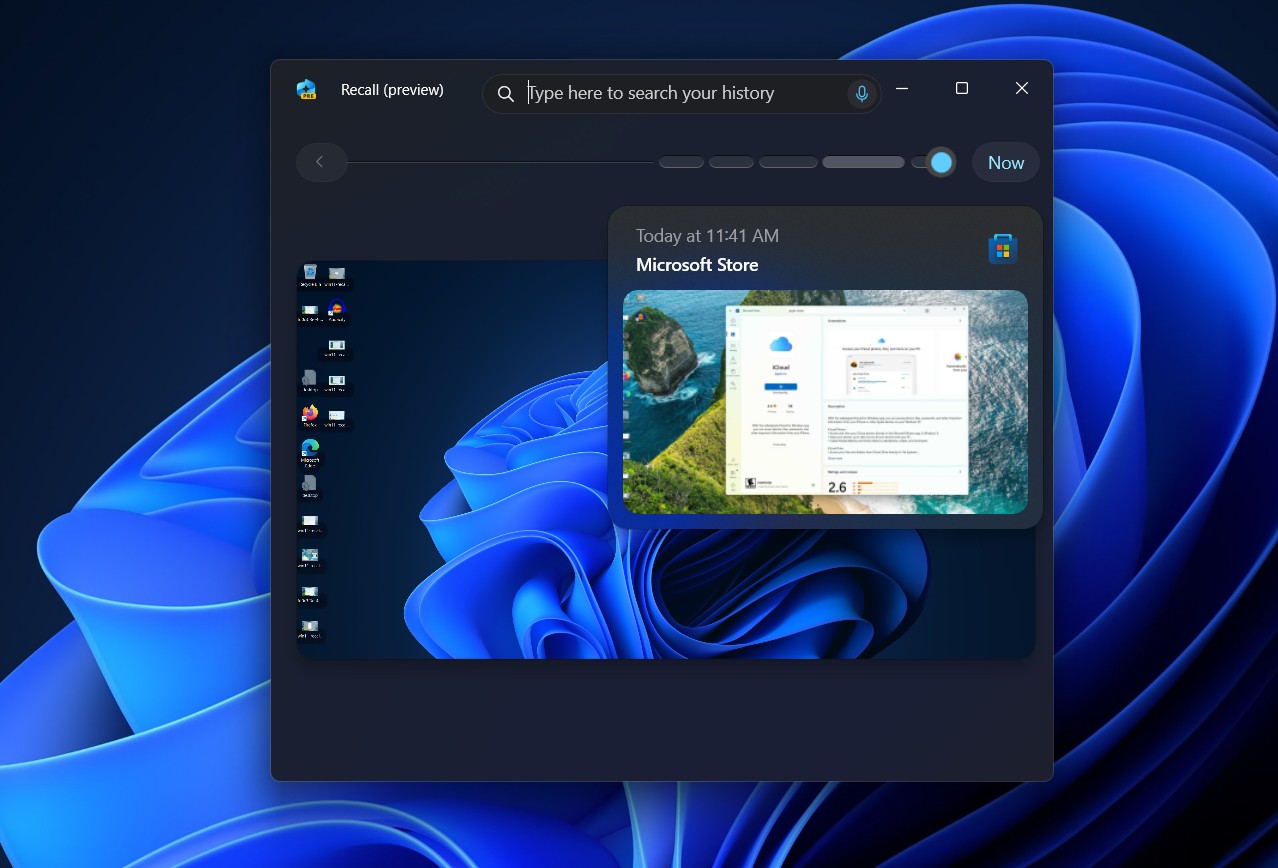

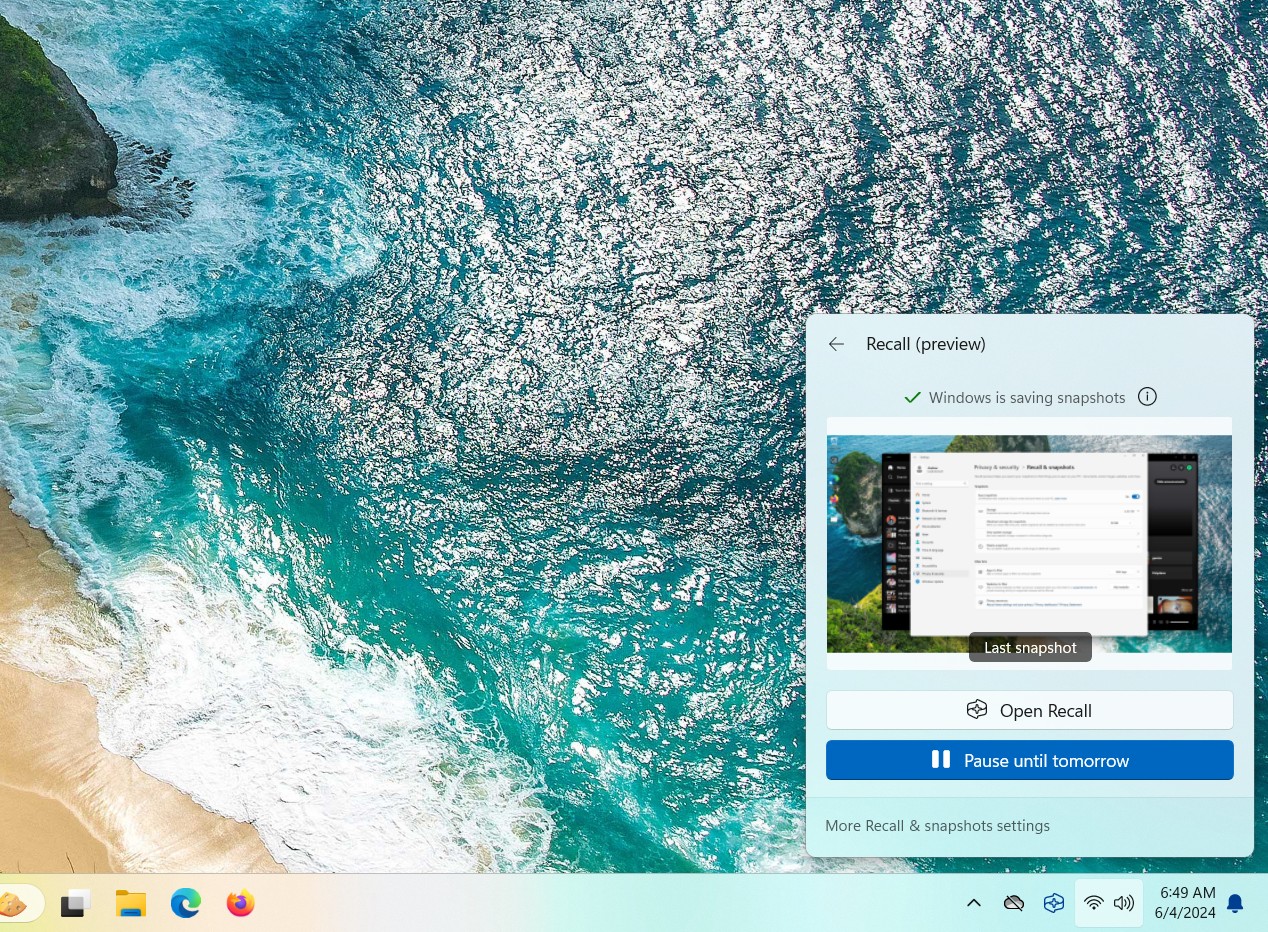

Microsoft’s Windows 11 Copilot+ PCs come with quite a few new AI and machine learning-driven features, but the tentpole is Recall. Described by Microsoft as a comprehensive record of everything you do on your PC, the feature is pitched as a way to help users remember where they’ve been and to provide Windows extra contextual information that can help it better understand requests from and meet the needs of individual users.

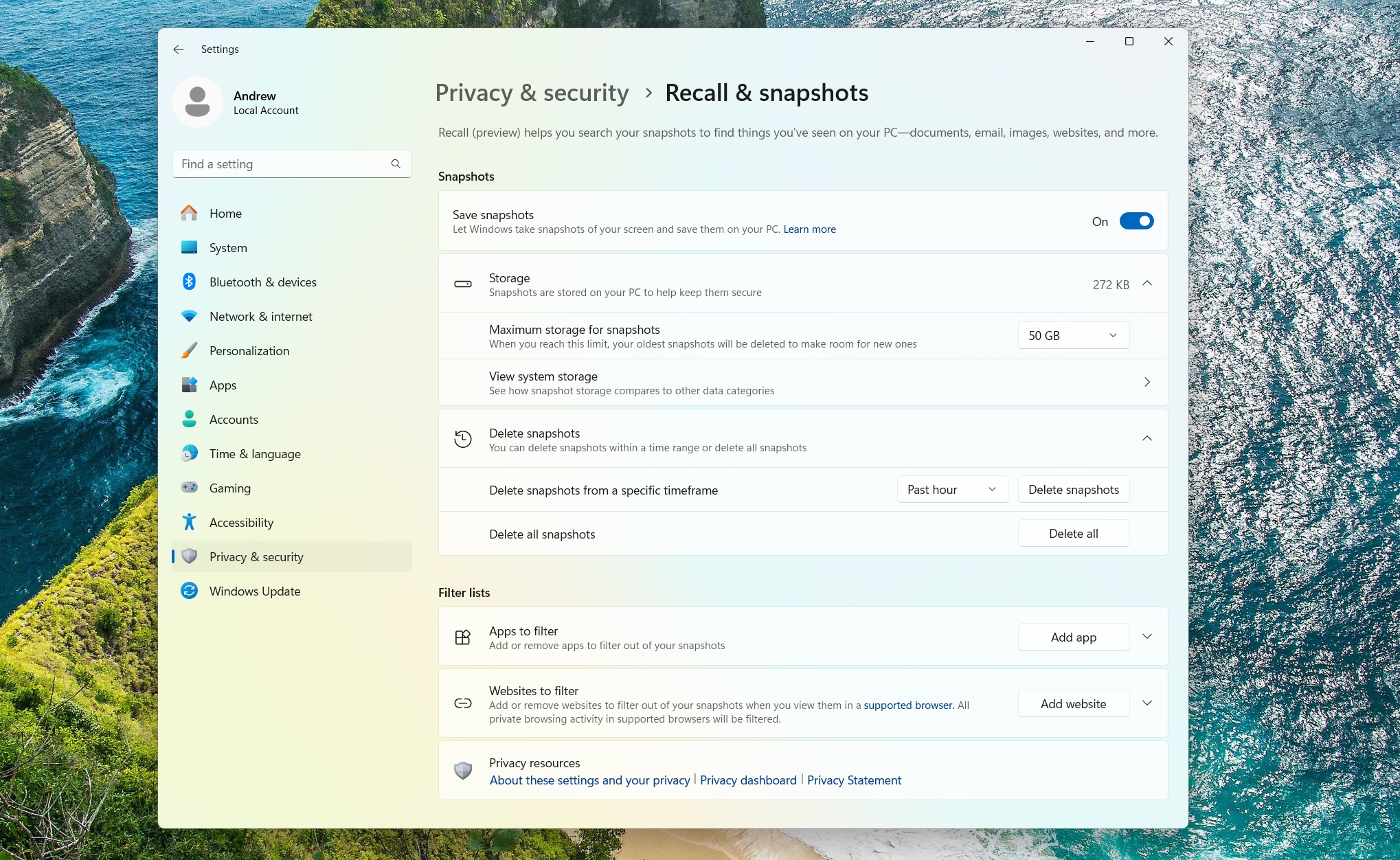

This, as many users in infosec communities on social media immediately pointed out, sounds like a potential security nightmare. That’s doubly true because Microsoft says that by default, Recall’s screenshots take no pains to redact sensitive information, from usernames and passwords to health care information to NSFW site visits. By default, on a PC with 256GB of storage, Recall can store a couple dozen gigabytes of data across three months of PC usage, a huge amount of personal data.

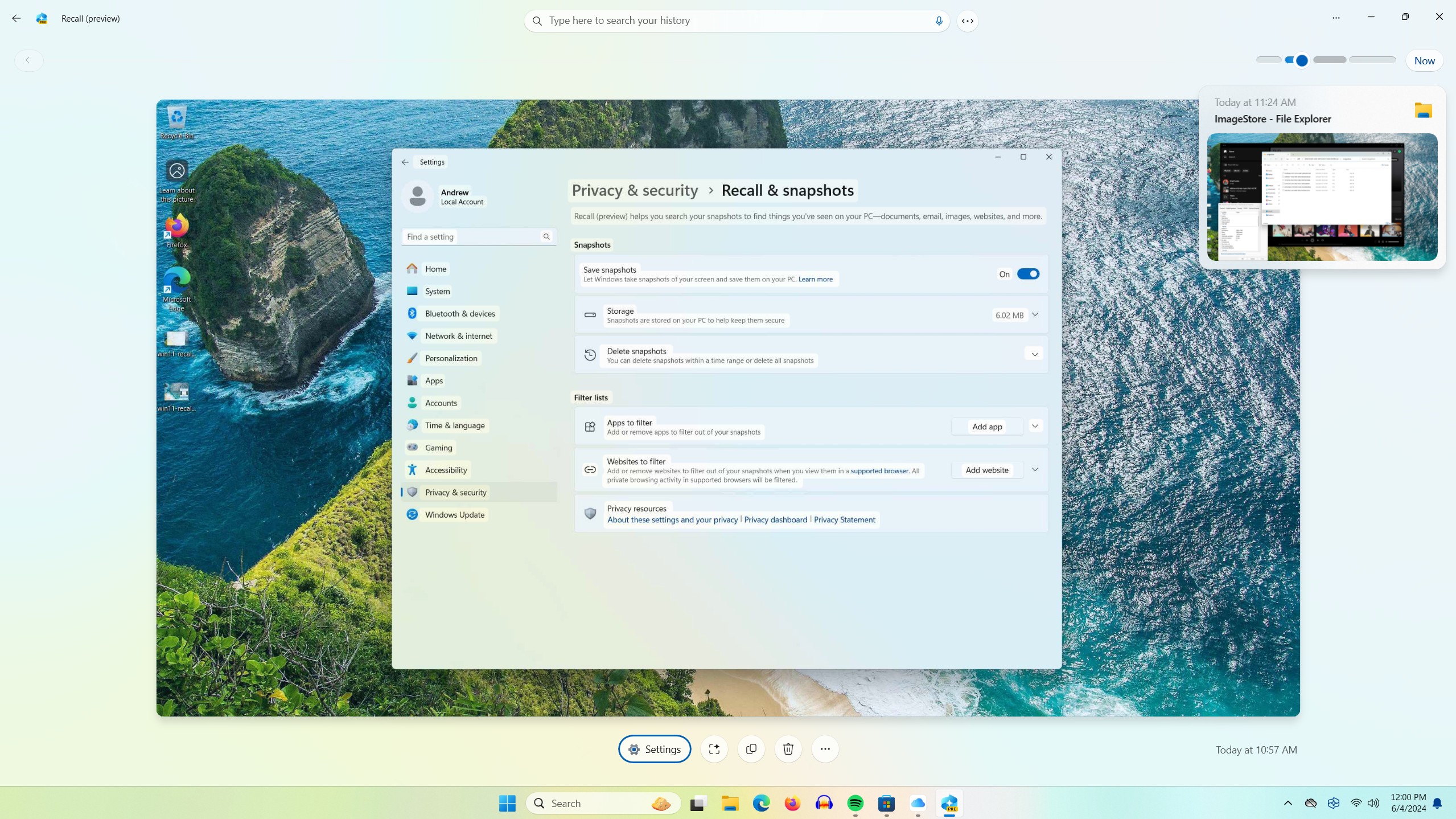

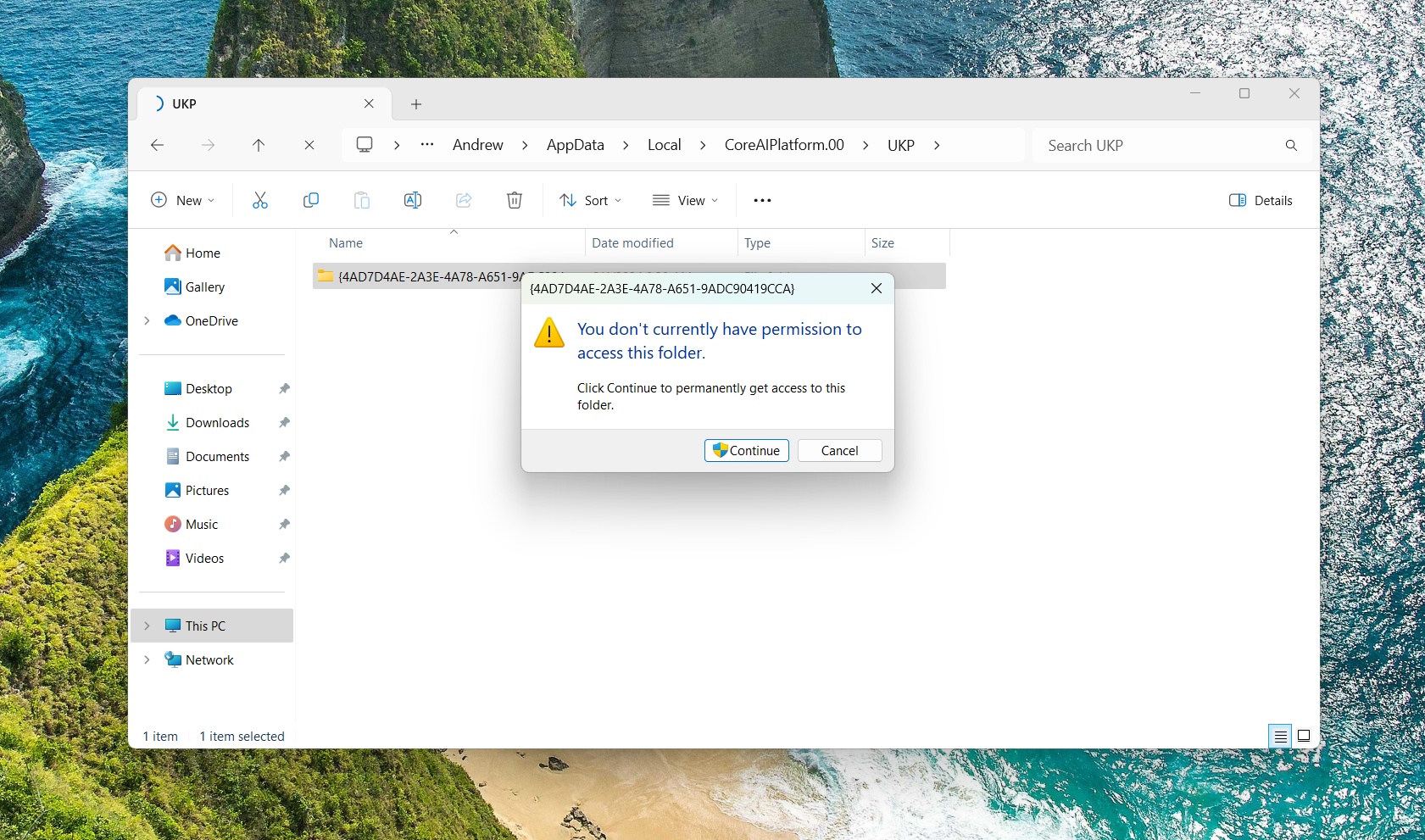

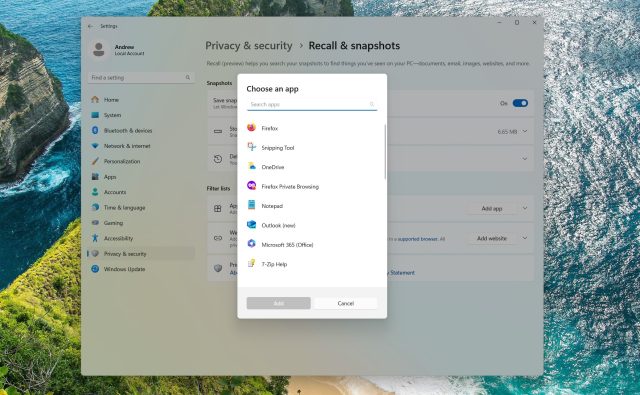

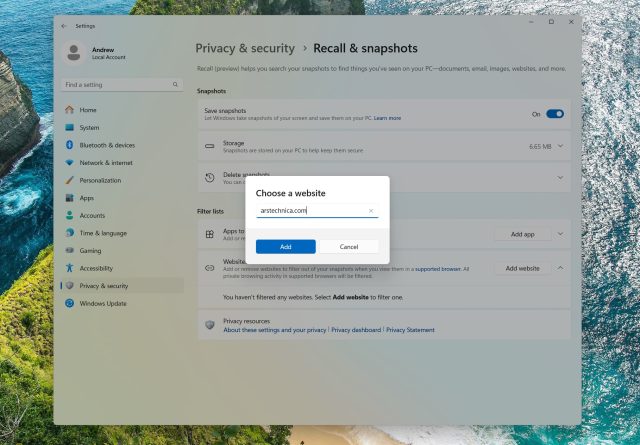

The line between “potential security nightmare” and “actual security nightmare” is at least partly about the implementation, and Microsoft has been saying things that are at least superficially reassuring. Copilot+ PCs are required to have a fast neural processing unit (NPU) so that processing can be performed locally rather than sending data to the cloud; local snapshots are protected at rest by Windows’ disk encryption technologies, which are generally on by default if you’ve signed into a Microsoft account; neither Microsoft nor other users on the PC are supposed to be able to access any particular user’s Recall snapshots; and users can choose to exclude apps or (in most browsers) individual websites to exclude from Recall’s snapshots.

This all sounds good in theory, but some users are beginning to use Recall now that the Windows 11 24H2 update is available in preview form, and the actual implementation has serious problems.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...

Sure, you can disable it on your machine. But since it's taking screen-grabs, you have to ensure that everyone else with whom you communicate has it disabled as well.

End-to-end encryption will be meaningless because it's taking screen-grabs at the end-points. That means Signal's security is borked, for example. For both ends, because the entire conversation appears in the app window on both ends. Doesn't matter if you exclude Signal from recording on your end.

You can't have any security unless you confirm that both ends have Recall disabled. Assuming it's really disabled when you turn it off, of course. And that the next OS update didn't turn it back on without telling you.